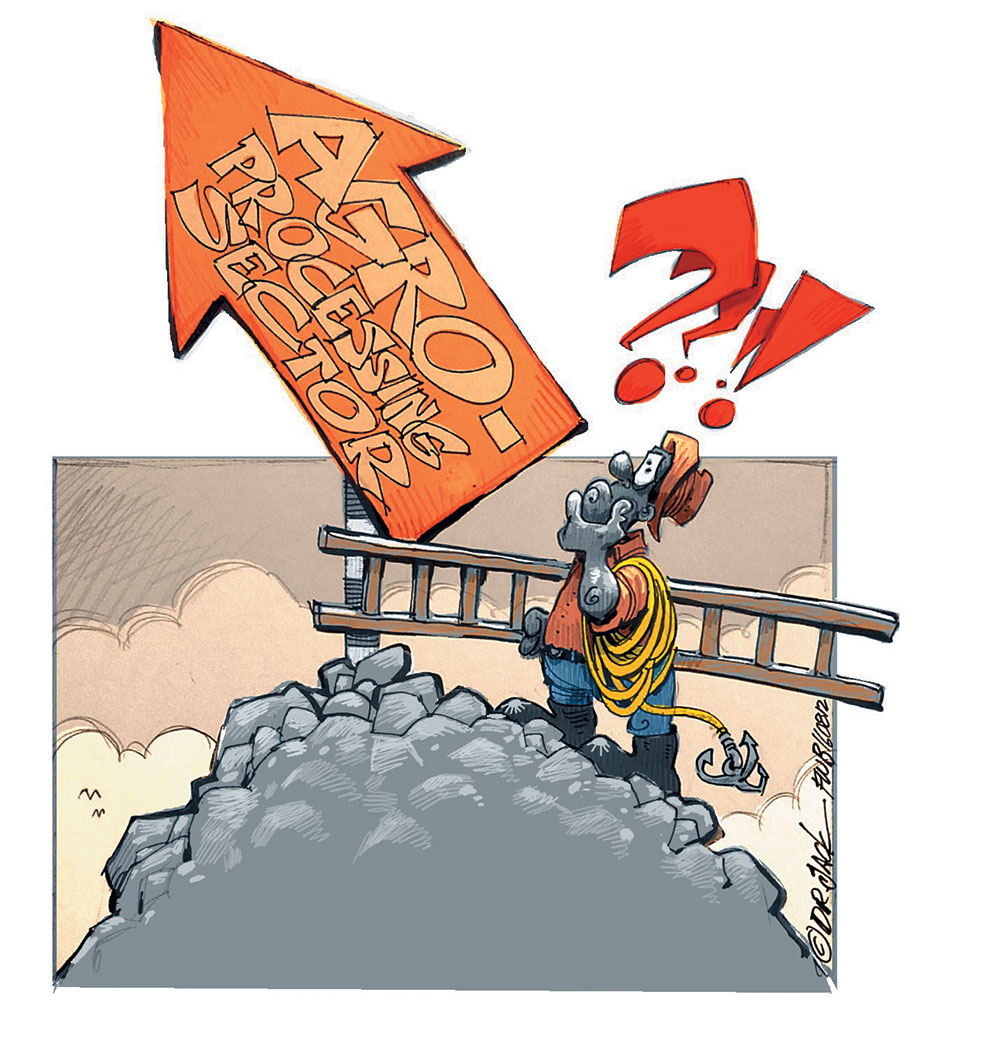

A study recently released by the Centre for Competition, Regulation and Economic Development (CCRED) at the University of Johannesburg examines the barriers to greater economic participation for South African entrepreneurs and black industrialists.

One of the areas investigated was obstacles to entry and expansion in the agro-processing sector and the importance of supermarkets as a potential market for new entrants.

Agro-processing is one of the manufacturing sector’s largest subsectors and continues to grow. Most government policies acknowledge that it is a critical driver of GDP growth, increasing exports, and new business formation. As such, this industry holds significant capacity and potential to generate inclusive growth.

Cartoon by Dr Jack

CCRED looked at three agro-processing sectors: poultry, dairy, and maize and wheat milling. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the findings show that many of the attributes of these sectors, which gave rise to concentrated markets and cartel conduct in the past, continue to discourage the entry of rivals. New businesses must contend with strong, entrenched social networks of insiders, and ongoing anti-competitive conduct, which can exclude them from full participation.

This is particularly true with respect to the way in which new businesses fit into the value chains and how they are governed. For example, cases before the Competition Commission led to vertically-integrated poultry producers being prohibited from explicitly requiring a buyer of poultry breeding stock to also buy its animal feed. But general practice to sell feed ‘specifically formulated’ for a particular breed continues. This locks the buyer of breeding stock into a particular producer for feed as well.

Financial obstacles

The poultry value chain is further characterised by high working capital requirements and a lengthy production cycle. New poultry producers need up to two years’ worth of capital to sustain their business before they earn revenue from the sale of their first commercial broilers. Poultry production also requires a high level of coordination between the various levels of the value chain. Its perishable nature makes access to markets a crucial issue.

With respect to milling, new entrants have expressed concern about a lack of support from industry associations and the high costs of doing business with silo owners, who have long-standing relationships with large firms.

New millers are also unable to invest in trading capabilities in order to use the Safex system optimally, and working capital is often tied up as ‘deposits’ against which they purchase grain from silo owners.

In dairy, the scale and significant capital costs required to build a milk processing plant that can handle peak capacity but remains under-utilised in the low season, is a barrier to entry for processors.

At the same time, processors still wield significant power over farmers. Coega Dairy was established when a group of farmers joined forces to successfully enter the dairy processing arena, thus ensuring security of supply and greater control over margins along the entire value chain.

New entrants to all value chains mentioned the difficulty of getting their products to consumers. The formal grocery retail market in South Africa is dominated by large supermarket chains occupying prime retail space. Their positions in these prime sites are often protected by long-term, exclusive leases with property owners.

New processors must endeavour to get their products listed in the major chains to build a sustainable customer base. However, to have their products listed, they are often expected to make significant ‘listing’ payments.

In addition, they often have to make an up-front commitment to in-store marketing and advertising campaigns, employ merchandisers who ensure that their products are stocked on supermarket shelves, and invest in logistical capacity to deliver their products to supermarkets’ regional distribution centres.

Furthermore, they have to pay a range of other costs incorporated into their trading terms, as well as adhere to quality standards of individual supermarkets. Collectively, these result in high cost implications and create challenges that are often insurmountable for small processors.

Overcoming barriers to entry

The Massmart Supplier Development Fund, established as part of the Walmart/Massmart merger to develop new and black-owned suppliers, has been partially successful in addressing some of these barriers to entry.

It essentially reduces the common challenges new entrants face in terms of identifying a market, accessing formal retail channels, securing good shelf-space, building a customer base, establishing the quality perception of the brand, and overcoming cash flow problems and listing fees. During its first two years, it has facilitated entry and expansion of 24 manufacturing firms and 139 small- scale farmers and farmer cooperatives.

As a consequence, one of the study’s recommendations is to give the competition authorities greater leeway in imposing alternative remedies for anti-competitive behaviour, in order to facilitate entry and contribute to competitiveness.

Another suggestion from the CCRED study is that support for agro-processing entrants should take a value-chain approach and pay particular attention to how new firms will get their products to consumers. This could be achieved by facilitating access to distribution channels of established players, facilitating voluntary codes of conduct between producers, wholesalers and retailers to improve the functioning of the food chain.

Investing in formal supplier development programmes, providing financial assistance, and training subsidies to small suppliers, were among the other recommendations.

The views expressed in our weekly opinion piece do not necessarily reflect those of Farmer’s Weekly.

Reena das Nair is lead economist at Acacia Economics and senior researcher at the Centre for Competition, Regulation and Economic Development (CCRED), University of Johannesburg. Tamara Paremoer is an economist at Acacia Economics and senior researcher at CCRED.

Read the full report >>> Competition, barriers to entry and inclusive growth: Agro-processing